Understanding Humor In The Real World

Comedic Conflict (Lesson)

Comedic Conflict (Compilation)

The Mechanics of Comedy

This article is an abridged version of the Chapter 2 of Playfully Inappropriate.

In this section, we’re going to be looking at the underlying mechanics of comedy. If you’ve studied comedy before, you probably know a lot of the tactics that are out there. You probably know many of the strategies that comedians employ in order to get laughs. But if you’re like most, you probably don’t know the underlying mechanics of why they actually work.

Here’s why this is so important: comedy is 100% natural. It’s what you already do when you’re being funny. It’s not an external system that you need to learn. Throughout Faster & Funnier, I’ll show you countless examples of how comedic conflict creates humor naturally and how great comedians get audiences laughing the same way people make their friends laugh.

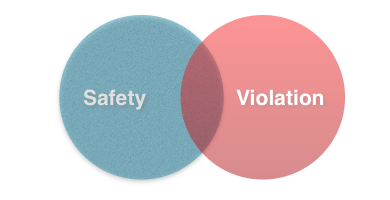

Humor is made up of two components: safety and violation.

Comedic conflict is the overlap between safety and violation. Violation by itself is too threatening, but a completely safe space has no tension. It’s too mundane and boring. If I told you a story about walking up the stairs and nothing actually happened in the story, that would be really boring. It’s completely safe. Nothing violated your expectations, assumptions, etc. But the opposite can be a problem as well. If I tell you a story that you clearly don’t believe is true (i.e., “I use to be a ninja”) then there’s too much violation. My story is so unbelievable that I won’t be able to create enough safe space to get a laugh. Both stories lack comedic conflict: what comes from combining safety and violation at the same time.

Think of comedic conflict as the sweet spot for a comedian. Here’s a great way of illustrating how this works. Let’s take the example of tickling. What would happen if you tried to tickle yourself? Well, because there’s no violation happening, because it’s 100% safe – there’s no tension since you’re doing it to yourself. On the other hand, you wouldn’t enjoy the complete violation of being tickled by a creepy stranger, because you would feel extremely unsafe. Getting tickled is only funny when you’re not 100% in control, but the person doing it doesn’t feel like a threat. That’s comedic conflict.

Comedic Conflict in Jokes

Let’s take a look at the original jokes to see how comedic conflict works in conventional jokes.

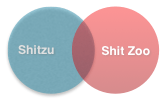

‘I went to the zoo the other day, there was only one dog in it, it was a shitzu.’

The humor comes from shifting the audience member from safety into violation. The setup creates the first circle (usually safety) and the punchline “breaks the audiences assumptions” by pushing them into the second circle (violation).

The second understanding reveals the comedic conflict. There’s an overlap between safety (Shitzu) and violation (shit zoo). The quick switch allows for both ideas to be in the audience’s head at the same time. The humor doesn’t come from shitzu or shit zoo, it comes from the juxtaposition (combination/overlap) of them.

Here is another great example of a violation that feels safe.

A woman gets on a bus with her baby. The bus driver says: ‘Ugh, that’s the ugliest baby I’ve ever seen!’ The woman walks to the rear of the bus and sits down, fuming. She says to a man next to her: ‘The driver just insulted me!’ The man says: ‘You go up there and tell him off. Go on, I’ll hold your monkey for you.’

In this bus joke, there was a clear violation against the lady. But why do we laugh instead of get angry at his rude comment? The laugh comes from the innocence of it. The man is clearly coming from a safety POV because the man says: “You go up there and tell [the bus driver] off.” So the man is clearly on the woman’s side. But then he says something worse. We don’t laugh because he’s innocent or because he violated a social norm. We laugh because he did both at the same time.

This is why children can get away with saying crazy things. Their childlike innocence provides a HUGE amount of safety while they say something that, if it came from an adult, would just be a clear violation.

Violation

First, all types of humor begin with some type of violation. Here are some great examples of the types of violations comedians find effective.

Violation of a norm: A good example is a cultural norm. This viral commercial for Poo-Pouri (video) got its comedic power from violating a cultural norm.

Linguistic violation: The most basic type of these violations is the pun, a play on words.

Violation of our predictions: This is the basis of the three-count joke formula, where you have a list of three things and the first two are normal, setting a pattern, before the third surprises us.

Three guys, stranded on a desert island, find a magic lantern containing a genie, who grants them each one wish. The first guy wishes he was off the island and back home. The second guy wishes the same. The third guy says, “I’m lonely. I wish my friends were back here.”

Safety

Comedic conflict doesn’t just come into existence with a violation. It requires some kind of safe space. Humor can’t be seen as threatening. Look at Lewis Black or Sarah Silverman and you can see that even though they might appear to be very aggressive in their material or performances, there is still a lightheartedness about the way that they present their material.

Sarah Silverman can get away with a lot of material that really pushes the boundaries of what’s acceptable. The reason that she can do that is because her personality on stage creates a safe place in which we don’t feel like we have to take her words as threatening.

Another comedian that’s great at pushing this boundary is Anthony Jeselnik. His laughs usually come from how far into a violation he can take the audience while still being liked. But throughout the set, there’s a calmness to the delivery that helps create a place where the audience feels safe laughing at what many of them probably consider to be horrible things.

I met a girl at a bar. She said she was a brain surgeon… I don’t know if this makes me sexist, but I was really impressed… Most women… can’t pull off sarcasm.

The same is true for Jim Jefferies (“Bill Cosby” video). He creates safety with how he says his material while the material is often a clear violation.

My one skill in life is being able to say horrible things and still be ‘likable.’ If you take out the whole (sarcastic dance)… And just read my material… it’s a BAD READ!

Another comedian who excels at creating a safe space even with edgy material is Amy Schumer (“High School Crush” video). In this bit, she does material on a topic that most open-mic comedian would fail at… pedophilia. But she does two things that make the topic acceptable to the audience. First, she brings a playful, lighthearted innocence to the story. Anything overly creepy would have likely been rejected by the audience as too much of a violation. Second, she doesn’t go into any specifics.

Even with a playful comedian, the audience still has boundaries. Keeping the topic vague helped keep it safe. Demetri Martin (“12 Year Olds” video) used this very idea to create humor.

“You can say ‘I love kids’ as a general statement. It’s when you get specific that there’s a problem… … ‘I love 12 year olds.”

So it’s absolutely mandatory that early on in our set, we create some kind of a safe space in which the audience understands it does not need to feel psychologically or physically threatened, even if our humor gets dark. Comedians only succeed when there’s a balance between them. Brian Regan’s violations are very different from Amy Schumer’s, but both have found an effective balance.

If you go to an open mic and witness a particularly dirty set of jokes by a comic, you’ll see something interesting. A dirty joke fails to get a laugh because it throws the audience too far into violation without creating a safe space. If the comedian continues using too much violation and not enough safety, the audience will try to bring themselves back into balance. Many times they’ll let out a nervous laugh… but not because they liked the joke. You’ll also see a few people check their phone, even though they know they don’t care what it says. They’re releasing stress built up from the violation.

Had the comedian done his job, the stress would have been released by the punchlines. The tension created by the violation must go somewhere. Awkward laughs and checking phones are just a way of disengaging from the tension of the moment and creating their own safe space.

People do the same thing while watching horror movies. When a horror movie gets particularly scary/stressful, a lot of people “create their own safe space” by disengaging (looking away, checking the phone, etc.). Comedic tension is subject to the same rules as other types of tension. An audience might laugh because something is funny or because they’re stressed. Either way, the tension has to go somewhere.

SAFETY + VIOLATION = COMEDIC CONFLICT

Creating comedic conflict is where many new comedians fail. If you sit at your computer with a neutral point of view, look around the room, choose a random object, and try to write about that object humorously, it’d be very difficult. That neutral point of view would make it extremely tough. Where would the comedic conflict be? Where is the violation? You look around the room and only see mundane things that are safe.

When you’re having difficulty pulling the humor out of your writing, very often it’s because you’re lacking comedic conflict. Your point of view is the main way that you go about creating this comedic tension. When you lose that, you lose your main source of comedic conflict.

This is why comedy teacher’s advice to begin a writing session by brainstorming topics is awful.

It’s counterproductive for two reasons:

Any comedic conflict must be “made up.” You might be able to make it sound a little natural… but it’ll most likely come out very forced and unnatural. Anything you write from an inauthentic beginning will most likely end up just as inauthentic.

Brainstorming is a disastrous creative strategy. Creativity researchers have found over and over again that brainstorming actually damages creativity rather than helps it.

So our number-one job when we get on stage is not to get a laugh as quickly as possible. Our first job is to shape our comedic space. Many times that means getting a laugh… but many times it doesn’t. Our main goal is instead to find our sweet spot. It’s to begin shaping our comedic space so that the audience trusts us but there are also some comedic conflicts to explore. We have to occupy a space in which there is safety/trust and violation, in order to establish good comedic conflict.

Stephen Wright (“Intro” video) does an amazing job at shaping his comedic space early on. Even with a very low energy, monotone delivery, he sets himself up for success very quickly. By the time he gets to the first laugh, the audience is already craving it.

“I’m feeling kinda hyper.”

One of the most impressive displays of playing with an audience’s sense of safety and violation comes from an Eddie Izzard (“Engleburt Humperdink” video) bit about British singer Gerry Dorsey changing his name to Englebert Humperdinck.

The first half of the bit is how he imagines he and his manager settled on the name “Englebert Humperdinck.” After the bit has run its course he gets very serious and says that Humperdinck died just before the show started. Izzard sells the line well enough that the audience isn’t sure if he’s actually telling the truth or not. It (purposefully) doesn’t feel like a joke.

… but he’s dead now. Did you hear that? Yeah… Today on CNN, I heard as I was coming out. Very weird. Cause it was Frank Sinatra recently as well. No — This is what I heard on the TV when I was coming out… … [laughing] It’s not true … … … [serious] No it is true… He was in a car and someone hit him… or something. … … [shakes head “no”] … … … … [nods “yes”]